Though autonomous driving technology is rapidly advancing, it’s difficult to assess whether driverless cars are actually safer than human-driven vehicles.

There’s a lot of momentum for autonomous vehicles right now. Companies like Waymo, Cruise, and Zoox have unveiled driverless ride-hailing services in select cities. Mercedes-Benz is poised to be the first automaker to put a car with conditional automated driving on the market. Though there’s plenty of hype, the industry keeps hitting a particular wall: Are these vehicles actually safe?

The Public Doesn’t Trust Autonomous Vehicles

While plenty of people are interested in autonomous vehicles (AVs), the general public remains wary of the technology. Companies hoping to bring AVs directly into public life can easily drum up enthusiasm, yet there’s still a disconnect when trying to turn that excitement into confidence.

Significant Press for AV Crashes Plays a Role

Part of consumers’ hesitancy comes from detailed reporting on autonomous vehicle crashes over the past few years. In fact, safety regulators reported that in 2021 and 2022, there were close to 400 AV-involved crashes. Perhaps the most famous accident is the 2018 autonomous Uber vehicle that struck and killed Elaine Herzberg in Tempe, Arizona. That case is back in the news five years later as Rafaela Vasquez, the driving assistant who was in the vehicle, recently pleaded guilty to endangerment.

The news hasn’t exactly slowed down, either. In October 2023, a self-driving vehicle operated by Cruise ran over a woman in San Francisco. The woman, whose identity has not yet been publicly revealed, was struck by another driver in a hit-and-run, which launched her into the path of the oncoming AV. Though the Cruise vehicle aggressively braked, it stopped on top of the woman, severely injuring her. That incident, along with a few others involving Cruise vehicles, led the California Department of Motor Vehicles to order Cruise to remove its cars from roads. The state also suspended the company’s driverless testing permit, effectively ending Cruise’s autonomous ride-hailing service.

PAVE Survey Results

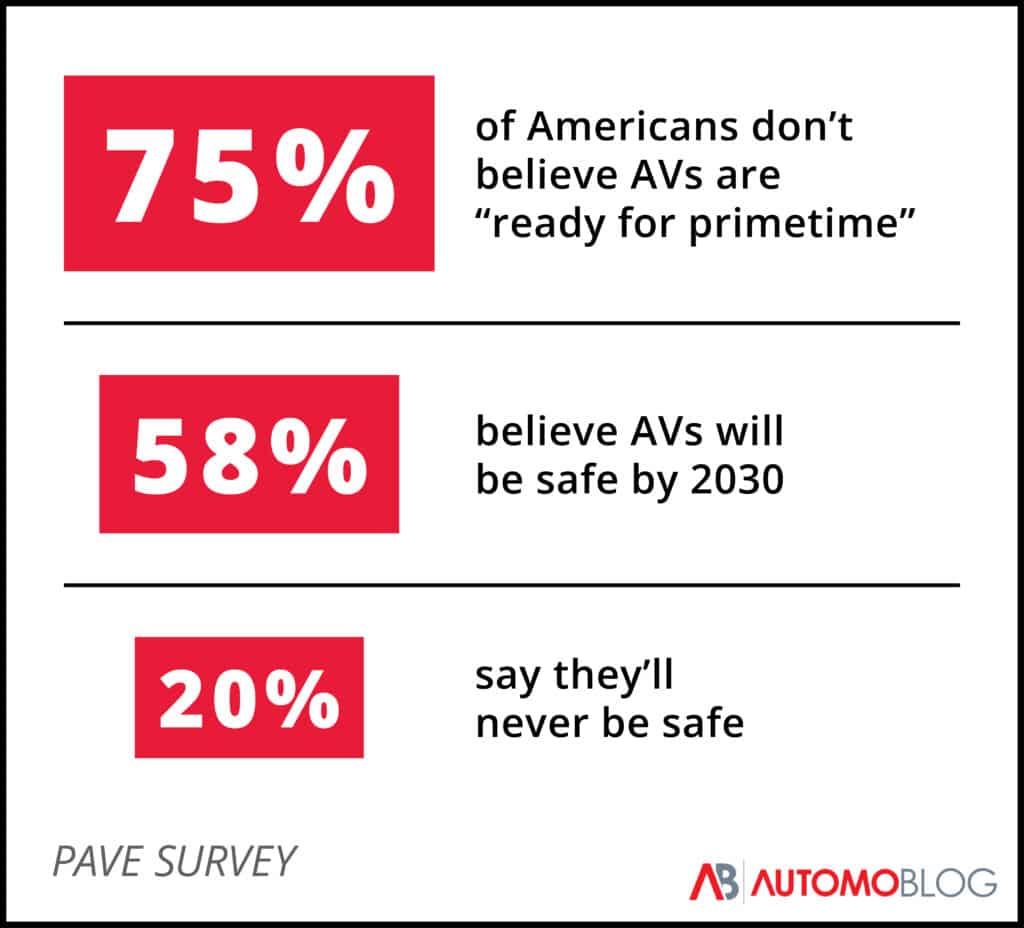

In 2020, Partners for Automated Vehicle Education (PAVE), a coalition of industry leaders, nonprofits, and academic advisory groups that promotes understanding of autonomous vehicle technology, conducted a survey of 1,200 Americans to assess the public attitude toward AVs. The survey found that respondents were strongly skeptical about the current state and safety of autonomous vehicles, but seemed open to the technology as a whole.

Nearly 75% of respondents thought that AVs are “not ready for prime time,” and almost half of those polled said they wouldn’t get in a driverless taxi. However, 58% of those surveyed believed that driverless cars would be safe by 2030 – though a solid 20% thought AVs would never become safe.

Though some of the apprehension comes from widespread publicity around accidents that involve autonomous cars, it’s not solely caused by these incidents. Most people said they simply don’t understand the technology enough to trust it. In fact, 60% of those polled said that they’d likely trust AVs more if they had a better understanding of how the technology works. Others said they’d trust AVs more if they were primarily used for moving cargo, could only travel at slower speeds, or had significant government oversight.

It’s worth noting that respondents held a much more favorable attitude toward advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). This technology includes GM’s Super Cruise™, Ford’s BlueCruise, and Toyota’s Safety Sense™ and is classified as Level 2 autonomous technology. The overwhelming majority of those polled believe that ADAS increases vehicle safety, suggesting that a gradual shift toward driverless technology could be successful.

AAA Survey Results

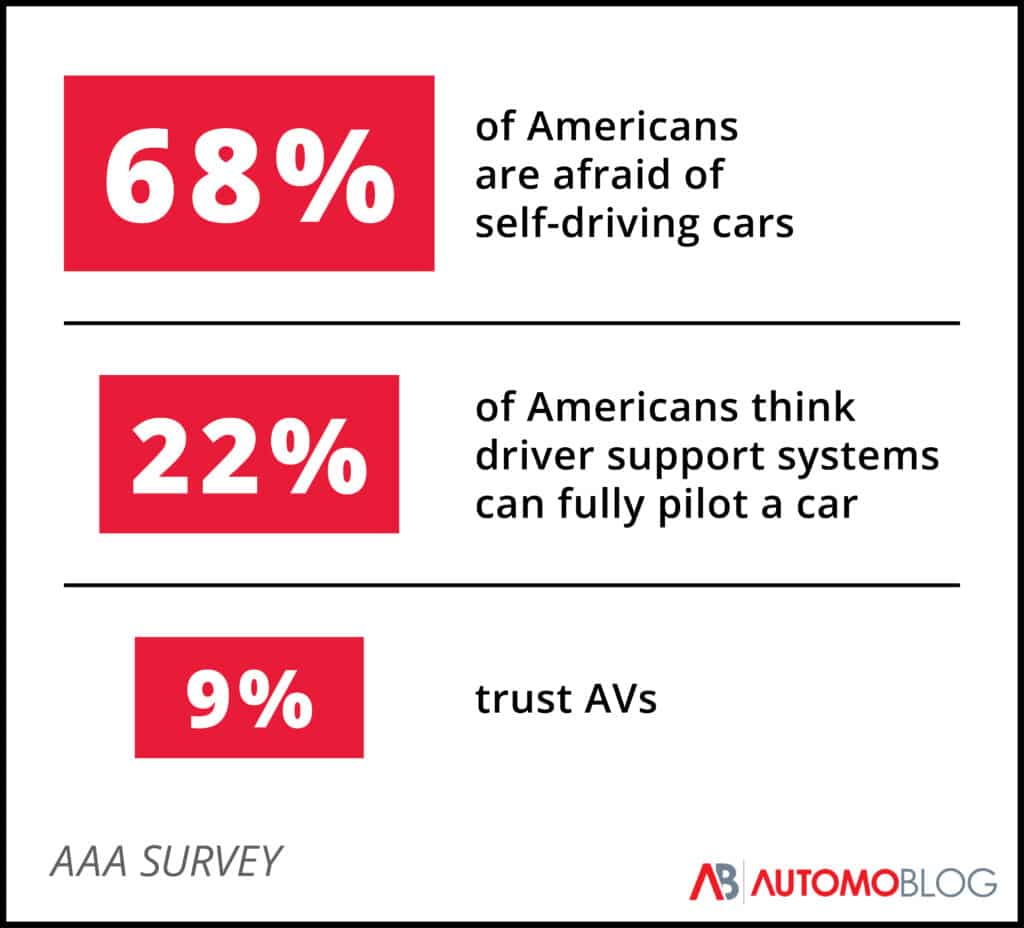

Since 2016, AAA has conducted annual surveys concerning autonomous vehicles to learn about public sentiment. The results of its 2023 survey, released in March, showed an increase in apprehension about driverless cars.

In 2020, 59% of respondents said they were “afraid” of self-driving vehicles. That number decreased to 54% in 2021 and 55% in 2022. It rose by a whopping 13% from 2022 to 2023, as 68% of those surveyed reported being afraid of autonomous cars. Though Greg Brannon, AAA’s director of automotive research, said that the organization didn’t expect such a huge increase in fear of AVs, he explained that “with the number of high-profile crashes that have occurred from overreliance on current vehicle technologies, this isn’t entirely surprising.”

Besides the car crashes that make the news cycle, public trust in AVs suffers because of confusion over what’s available. About 10% of respondents believed they could purchase a fully autonomous car – one that would allow them to fully disengage from the driving process – though Level 5 technology isn’t even close to entering the market.

There’s also an issue with the names that automakers have given to ADAS. The AAA survey found that about a quarter of Americans believe that driver-assistance systems that include the word “pilot” in the name would allow the car to drive itself without any human input.

How Can Autonomous Vehicle Safety Be Measured?

While it’s impossible to make any one piece of technology 100% safe, we can assess how dangerous something is through study and comparison. As autonomous technology develops and grows in popularity, companies and associations have conducted studies to see how self-driving cars compare with human-driven vehicles.

Proponents of AVs like to point out that there are scores of human-driven vehicle accidents each day. Though AV crashes get more publicity, there are far fewer incidents involving driverless cars. This logic, however, neglects the fact that there are few autonomous vehicles on the road.

Joseph Young, director of media relations at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), says that a one-to-one comparison isn’t that simple. “One major challenge is differences in reporting,” he explained. “AV developers report even the most minor crashes, while crashes involving human drivers usually need to meet a police-reporting threshold of injury or a certain property damage amount. And even then, it’s well known that eligible crashes involving human drivers are underreported to police.”

IIHS Study Findings

Over the past few years, the IIHS has conducted studies to determine the safety of AVs as compared to human-driven cars. In 2016, the organization sought to compare crash rates of Google’s self-driving cars with those for human-driven vehicles. It found that overall, the Google AVs had lower crash rates than human-driven vehicles and got into different kinds of accidents. In most cases, the Google AV crashes were minor, most happening at speeds of 5 mph or less. It’s also important to note that these were test vehicles, so engineers monitored the driving and could take over at any moment. The IIHS is currently working to update this study.

The organization conducted another study in 2020 to learn the effects of human programming on autonomous vehicles. Automation has long been touted as the answer to traffic accidents as, in theory, it would eliminate the kind of mistakes that all drivers make.

“We know that plenty of humans make mistakes that lead to crashes that aren’t necessarily related to perception issues, so how many crashes AVs get into will likely come down to how ‘humanlike’ they drive,” Young said. “What [the study] found is that AVs … could struggle to eliminate most crashes. This is because many crashes that are attributed to human error are the result of deliberate actions, like choosing to speed or drive aggressively. If AVs are programmed in a way that allows these behaviors, then many crashes are still going to happen.”

The IIHS analyzed a national survey of police-reported crashes, and determined that 90% of them could be attributed to driver error. In its study, the organization found that one-third of those crashes could be prevented thanks to an AV model’s ability to perceive its surrounding environment beyond human capability. The other two-thirds of those accidents could be avoided if humans programmed AVs to prioritize safety over speed.

Waymo Study Findings

Waymo, a Google spinoff that operates driverless ride-hailing service Waymo One, partnered with Swiss Re, a leading reinsurer, to research the safety of autonomous vehicles. The study analyzed over 600,000 liability claims and data from over 125 billion miles driven to formulate a human baseline with which to compare AV data. Because Waymo One operates in San Francisco and Phoenix, Swiss Re looked at claims within Waymo’s operating ZIP codes.

The study compared Waymo’s liability claims with the human baseline put together by Swiss Re. It found that Waymo Driver technology reduced the frequency of property damage liability claims by 76% and decreased bodily injury claims by 100%.

While the results of this study suggest that AVs could become far safer than human-driven vehicles, it’s critical to consider the scope of the Waymo Driver. The technology is at Level 4, meaning that it only operates within a specific geographic area using geofencing technology. Waymo One serves 225 square miles of Phoenix, which is roughly 44% of the city’s land area. The service operates across all of San Francisco, but that’s only 47 square miles in total.

How Can We Keep Driverless Cars Safe?

As more autonomous driving technology rolls out, it will be imperative to study how it works and to make adjustments to programming and hardware. However, it will be just as critical to consider the environment around AVs. As driverless cars become more popular and readily available, changes to infrastructure will become increasingly necessary.

“Infrastructure elements that would make AV tech safer would benefit humans too,” Young said. “Better roadway maintenance, clearer lane lines at intersections, clearer lines of sight, better-protected and -lit pedestrian crossings.” Thinking about driving safety for humans and AVs as two distinct areas of concern may not be helpful for either one.

There’s also a need to create AVs that are equipped to handle more extreme environments, or spots that Young described as “regions with snow and extreme temperatures; regions with lots of rain; regions with lots of hills that interfere with line of sight of the roadway; regions with lots of animal strikes.” Complex urban roadways also pose challenges for driverless cars, especially if there are abrupt changes in traffic patterns.

The way to make driverless cars safe for riders, thus building enough public confidence to see widespread adoption, is to consider all factors at once. This may require more government regulation as well as increased partnerships between AV manufacturers and municipalities. Instead of solely focusing on technological advancement, help could come through better roadway construction, infrastructure updates, and less emphasis on speed.