Affiliate Disclosure: Automoblog and its partners may earn a commission if you purchase a plan from the car insurance providers outlined here. These commissions come to us at no additional cost to you. Our research team has carefully vetted dozens of car insurance providers. See our Privacy Policy to learn more.

Do majority-minority ZIP codes pay higher car insurance premiums than majority-white ZIP codes? The answer is yes, according to a massive 2017 investigative report published by ProPublica in conjunction with Consumer Reports. Reporters looked at ZIP codes in California, Illinois, Texas, and Missouri, and found many discrepancies in car insurance rates for various ZIP codes. This is despite the fact that nearly every state has laws that bar companies from using discriminatory rate-setting practices. The findings point to, as the report’s authors put it, “a subtler form of redlining.”

Though they researched insurance premiums in several states, the reporters focused mainly on Chicago – one of the country’s most segregated cities. In particular, ProPublica chose residents of two different ZIP codes: Otis Nash, who lives in the predominantly Black neighborhood of East Garfield Park, and Ryan Hedges, who lives in majority-white Lake View. After comparing their monthly and annual car insurance rates, reporters found that Hedges, like most residents of Lake View, paid significantly less for auto coverage than residents of minority-majority ZIP codes.

What ProPublica Discovered

There are a few key findings that back ProPublica’s conclusions. First, reporters looked at the claims paid out in each ZIP code by Illinois insurers. In Nash’s ZIP code, 60612, insurance companies paid out around $172 per vehicle each year from 2012 to 2014. In 60657, the ZIP code that contains Hedges’ neighborhood, insurers paid out about $216 per car during the same time period. The majority-white ZIP code received around 20% more in bodily injury and property damage payouts.

Zooming out, ProPublica’s investigators discovered that those in minority-majority ZIP codes spend roughly 11% of their household income on car insurance, which is more than double the 5% that those in majority-white ZIP codes spend. The U.S. Treasury Department considers car insurance to be affordable if it costs 2% or less of a household income – and while both populations are spending outside the affordability index, minority-majority ZIP codes typically spend quite a bit more.

| Chicago ZIP Code | Percentage of Black Residents | Percentage of White Residents | Average Monthly Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance | Average Annual Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance |

| 60612 | 61.7% | 24.9% | $189 | $2,276 |

| 60657 | 2.8% | 86.8% | $132 | $1,589 |

How Zoning Influences Insurance Rates

Insurance regulators took their cues from zoning laws, learning how to mask discriminatory practices with technical language that doesn’t mention race. Cities have long used what’s referred to as “exclusionary zoning” to keep low-income workers out of wealthier neighborhoods, usually by designating different minimum lot sizes and land usage for different neighborhoods. By only focusing on how land could be used in specific areas, zoning boards could avoid running afoul of the 1917 Supreme Court decision in Buchanan v. Warley, which ruled racial zoning unconstitutional.

In their 2018 paper, “Race, Ethnicity, and Discriminatory Zoning,” Allison Shertzer, Tate Twinam, and Randall P. Walsh looked at zoning laws in Chicago in 1920. They found that the Chicago Zoning Commission worked to increase population density in neighborhoods where Black people migrating from the South and other non-European immigrants settled. At the same time, the Commission supported a decreasing density in neighborhoods with more European immigrants or native-born whites.

In fact, the majority-Black or immigrant neighborhoods were at least five times more likely to be zoned for higher-density buildings in more industrial areas. This allowed the city government to reduce the value of minority-owned buildings and homes, thus reducing the ability of those residents to leave. Essentially, zoning was used to weaken economic opportunities in those neighborhoods.

Insurers can use zoned density to their advantage, pointing to ideas like “congestion” as reasons to charge more for coverage. According to Roger Wildermuth, a spokesperson for USAA quoted by ProPublica reporters, “Some areas may have slightly higher rates due to factors such as congestion that lead to more accidents or higher crime rates that lead to higher auto thefts.” Zoning helped corral a large number of people into small parts of the city, and insurers used that manufactured density to charge people in those neighborhoods much higher rates.

Why Do Insurance Rate Disparities by ZIP Code Persist in Chicago?

In the 1940s, the insurance industry agreed to state regulation in an attempt to be exempt from federal antitrust laws. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners helped craft legislation prohibiting discriminatory rate-setting practices, which was then passed by most states across the country. Though this legislation was a good step, it didn’t actually end these practices. Instead, it forced insurers to get more creative.

Again taking cues from zoning laws, insurance companies began dividing cities into specific areas. In 1969, Illinois began allowing insurers to issue auto insurance rates without being subject to regulatory approval, which led to companies dividing Chicago into four distinct rate-setting territories. East Garfield Park, along with much of the predominantly Black West Side, was effectively redlined. Insurers viewed those neighborhoods as higher risk and therefore charged residents higher rates for auto coverage.

A group of Black insurance brokers banded together in protest, eventually attracting the attention of the U.S. Senate Antitrust and Monopoly subcommittee. The Illinois legislature tried to address the issue but couldn’t agree, instead letting the open competition law expire. In 1972, the Illinois legislature passed a law barring insurance providers from using the four Chicago territories, instead requiring the city to be placed under a single territorial rate.

However, this single rate only applies to bodily injury liability rates, so insurers are still free to set property damage and other insurance rates by neighborhood or ZIP code.

Do Insurance Costs Differ by ZIP Code in Other Cities?

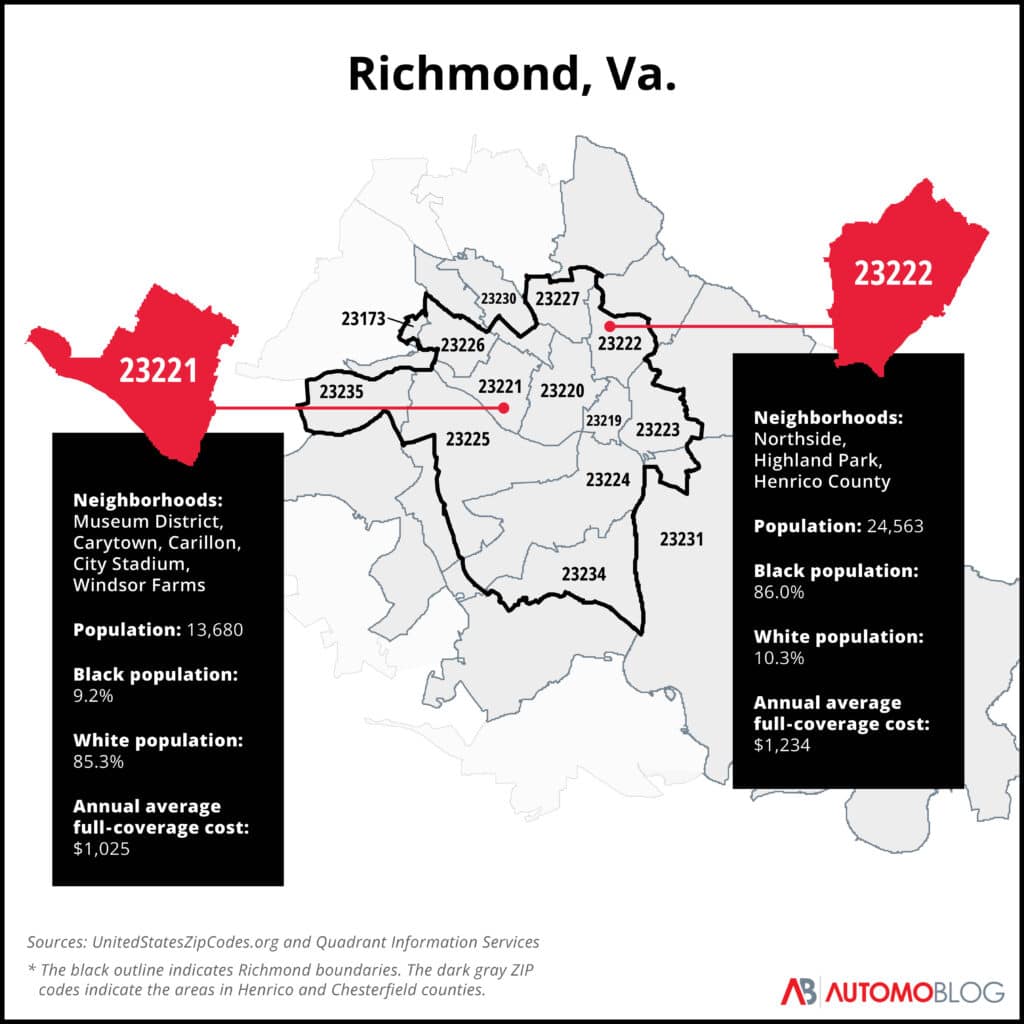

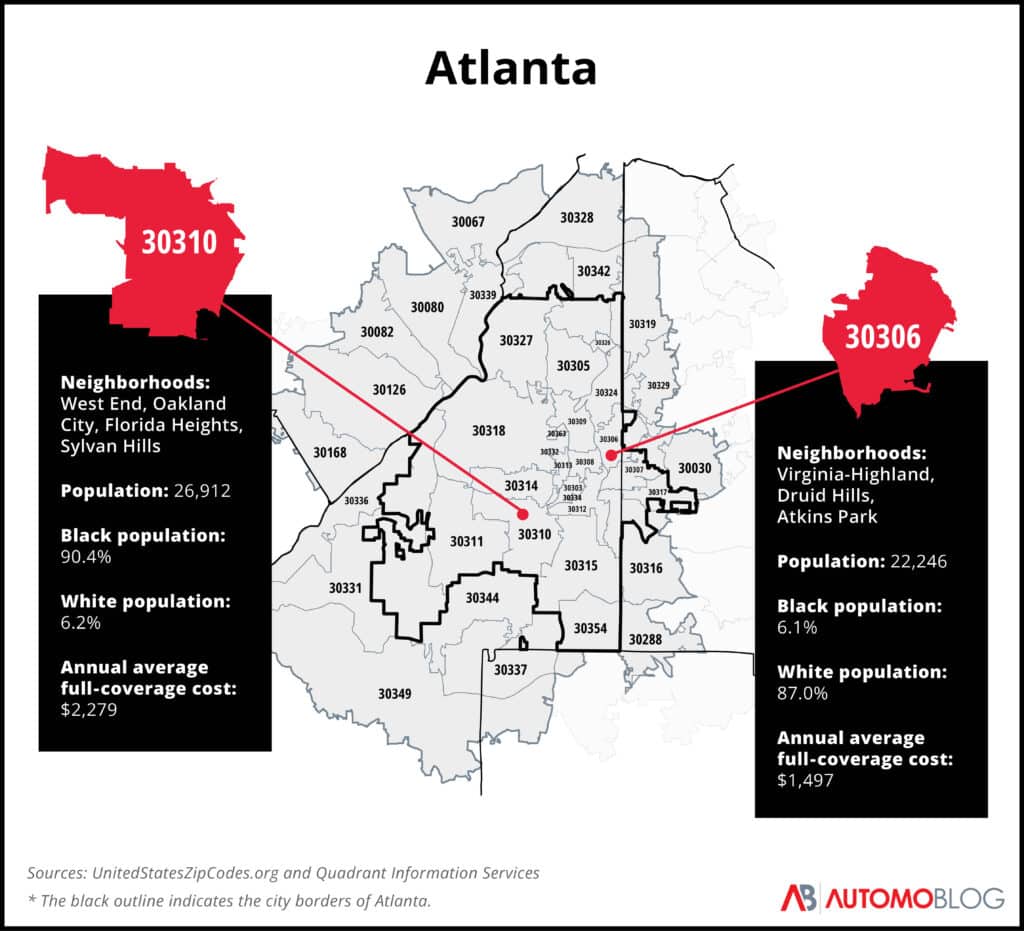

After looking at the most current data for the two Chicago ZIP codes, our Automoblog research team wanted to learn if the same trend was present in other cities. We chose two other notoriously segregated cities – Richmond, Virginia, and Atlanta, Georgia – and compared cost data from a majority-white ZIP code to a majority-Black ZIP code. Our data comes from Quadrant Information Services, an insurance analytics company.

Here’s what we found.

Richmond, Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia is divided into distinct counties and independent cities, meaning its cities are not part of a county. Richmond, the capital of the Commonwealth, sits between Henrico and Chesterfield counties, and some of its ZIP codes extend from the city into one of the surrounding counties. It ranks as the 38th most segregated city in the country.

The ZIP code 23221 is in the western part of the city, encompassing the neighborhoods of the Museum District, Carytown, Carillon, City Stadium, and Windsor Farms. About 85% of its nearly 14,000 residents are white.

The 23222 ZIP code encompasses all of the Northside and Highland Park neighborhoods and reaches into the eastern part of Henrico County. It has about 25,000 residents, 86% of whom are Black.

| Richmond ZIP Code | Percentage of Black Residents | Percentage of White Residents | Average Monthly Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance | Average Annual Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance |

| 23221 | 9.2% | 85.3% | $85 | $1,025 |

| 23222 | 86.0% | 10.3% | $102 | $1,234 |

According to our data, residents in 23222 pay about $209 more per year on average, or 20% more, than drivers in 23221.

Atlanta, Georgia

The Atlanta metro area sprawls into 11 different counties, but the city itself is in Fulton and DeKalb counties. It ranks as the 11th most segregated city in America.

The 30306 ZIP code is primarily in Fulton County, but parts stretch into DeKalb County. The ZIP code holds the neighborhoods of Virginia-Highland, Druid Hills, and Atkins Park, and has about 22,000 residents. The ZIP code is 87% white.

With a population of nearly 27,000 that is over 90% Black, 30310 is located on the west side of Atlanta. It includes the West End, Oakland City, Florida Heights, and Sylvan Hills neighborhoods.

| Atlanta ZIP Code | Percentage of Black Residents | Percentage of White Residents | Average Monthly Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance | Average Annual Cost of Full-Coverage Car Insurance |

| 30306 | 6.1% | 87.0% | $124 | $1,497 |

| 30310 | 90.4% | 6.2% | $189 | $2,279 |

The difference in car insurance rates for these two Atlanta ZIP codes is much more pronounced than the Richmond ZIP codes we researched. Residents of 30310 pay an average of $782 more per year for car insurance than those who live in 30306 – or an increase of over 50%.

How ZIP Codes Affect Insurance Rates: Conclusion

The ProPublica investigation is unfortunately the only of its kind, mostly because it’s difficult to collect this kind of information. The insurance industry isn’t especially keen on releasing data that shows how it sets rates or calculates risk in certain areas. States don’t gather this kind of data either; the authors of the ProPublica report filed records requests in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., but only four responded that they collected data on insurance rates by ZIP code. We reached out to city council members, aldermen, and insurance agents in Chicago, Richmond, and Atlanta, but no one was willing to comment on these practices.

Based on ProPublica’s investigation – which is now nearly a decade old – and our data from Quadrant Information Services, it’s clear that there is a disparity in how much insurance costs for people in different ZIP codes. But, because the insurance industry has a history of cloaking its motives behind “legal speak” that provides plausible deniability, it’s unclear whether this imbalance will change anytime soon.