Affiliate Disclosure: Automoblog and its partners may earn a commission when you use the services or tools provided on site. These commissions come to us at no additional cost to you. See our Privacy Policy to learn more.

A recent report from Counterpoint Research gave cause for optimism when it concluded that the current semiconductor shortage may come to a close as soon as “late Q3 or early Q4” this year. If that sounds familiar, it’s because this announcement is one of many over the last two years that have optimistically predicted an approaching end to the chip shortage for cars.

Despite many predictions that indicate the end may be in sight, the chip shortage is a complex issue with several moving parts. Global manufacturers, government entities, and more have worked to address specific aspects of the issue, but the many factors that influence the shortage make it challenging to accurately predict its conclusion.

Nobody Seems To Agree When the Chip Shortage Will End

Counterpoint offers plenty of data to support its predictions. The research firm analyzed production capacities alongside consumer demand to reach its conclusions.

However, others with similarly well-informed perspectives have come to drastically different conclusions. In April, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said he expected that the chip shortage would continue into 2024. Gelsinger cited supply chain issues with the manufacturing equipment used to produce semiconductor chips as the main roadblock.

Cristiano Amon, CEO of Qualcomm – one of Intel’s biggest competitors – has a more hopeful take than Gelsinger. In an interview with Fox Business, Amon said he could see a return to normal toward the beginning of next year.

“We still have more demand than supply, but we’re starting to see in the second half of 2022, a more balanced equation,” he told Fox Business. “I think as we enter 2023, we’re going to get out of the crisis.”

If the lack of consensus from major players in global industry is any indication, there’s still major uncertainty about when the chip shortage will end.

Manufacturing Capacity Is Expanding To Catch Up

A production capacity shortage is one of the primary causes for the chip shortage. Now, in addition to factories reopening, companies are building new semiconductor manufacturing centers worldwide to close the gap.

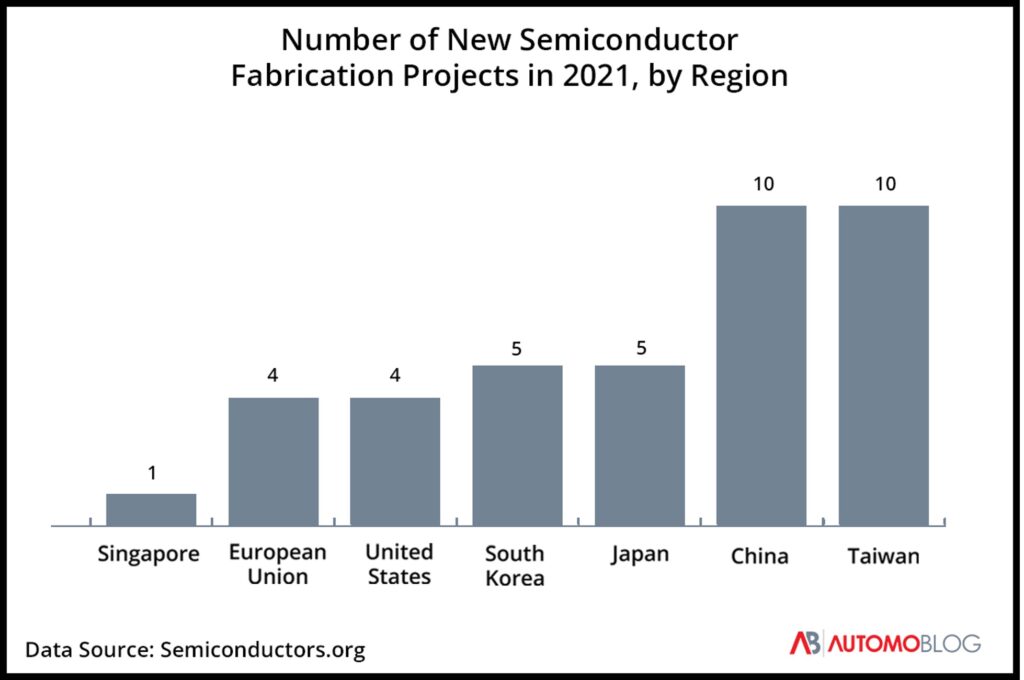

The vast majority of these new facilities are being built in Asia. China and Taiwan were already two of the world’s leading producers of semiconductors before the shortage, and the two account for more than half of the new facilities built in 2021.

Emerging Domestic Producers Face Challenges

While most new production facilities built since the beginning of the chip shortage are in Asia, production is ramping up in the U.S. as well. The country’s first silicon carbide chip plant opened earlier this year in April in Marcy, New York, and more of these facilities – or “fabs” – are on the way.

However, plans for an American resurgence in semiconductor manufacturing have hit a major roadblock. The current wave of investment in domestic chip manufacturing arrived on the heels of the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act, a bill that would offer as much as $52 billion in funding for domestic fab investment.

But Congress has yet to formally allocate the funds to support the bill. This has left companies that expected substantial subsidies as part of their investment in limbo – and some of them are starting to push back.

In June, Intel halted development of its Ohio plant indefinitely. Soon after, Taiwanese chip manufacturer GlobalWafers said its proposed $5 billion fab in Texas would only come to fruition if the bill receives funding.

However, on July 19, the Senate voted to move the funding bill forward. While the CHIPS Act still has a few steps to go before it can officially become law, its funding could help domestic fab producers make significant progress.

Production Capacity Isn’t the Only Issue

Although new production facilities address part of the issue, an increase in manufacturing capacity alone – no matter how large – won’t put an end to the chip shortage for car producers. Dr. Barbara Hoopes, Associate Professor of Business Information Technology at Virginia Tech University and supply chain expert, says that many of the hurdles to resolving the chip shortage have yet to arrive.

Hoopes says even with the opening of new fabs, building a domestic supply chain has several challenges. Among them is developing a workforce in an industry that is, in a practical sense, new in North America and the European Union (EU).

“Manufacturing capacity isn’t the only factor needed to ease the chip shortage,” she says. “The labor and talent pools will also take time to develop, both here in the U.S. and in the EU, which has also been largely dependent on Asian suppliers.”

Hoopes points out that the business side of a new supply chain – such as the formation of new partnerships, logistics build out, and transportation challenges – takes time to develop. How the government evolves around the burgeoning industry will also be a factor.

Other moving parts in the semiconductor supply chain face issues too. The ongoing invasion of Ukraine, for example, has severely impacted the availability of neon gas, a necessary component in chip manufacturing. According to Hoopes, increasing production capacity doesn’t solve those issues.

External Factors Also Play a Role in the Chip Shortage

While the world’s manufacturers scramble to address the supply side of the chip shortage, the demand side of the equation also plays a role. Some signs point to changes in demand emerging as well.

Demand for Vehicle Semiconductors May Drop

Supply chain issues like the chip shortage are among the many factors that have contributed to runaway inflation in recent years. Hoopes suggests that as the Federal Reserve raises the federal interest rate in an attempt to curb that inflation, demand for semiconductors could slow down.

“Interestingly, higher interest rates and inflation may cool consumer demand for many of the products that contain the semiconductors,” she says. “Weakening demand for consumer electronics and other products as a result of these factors may make more chip production capacity available to auto manufacturers to ease the existing production backlog.”

Supply Inequality Could Exist Between Countries

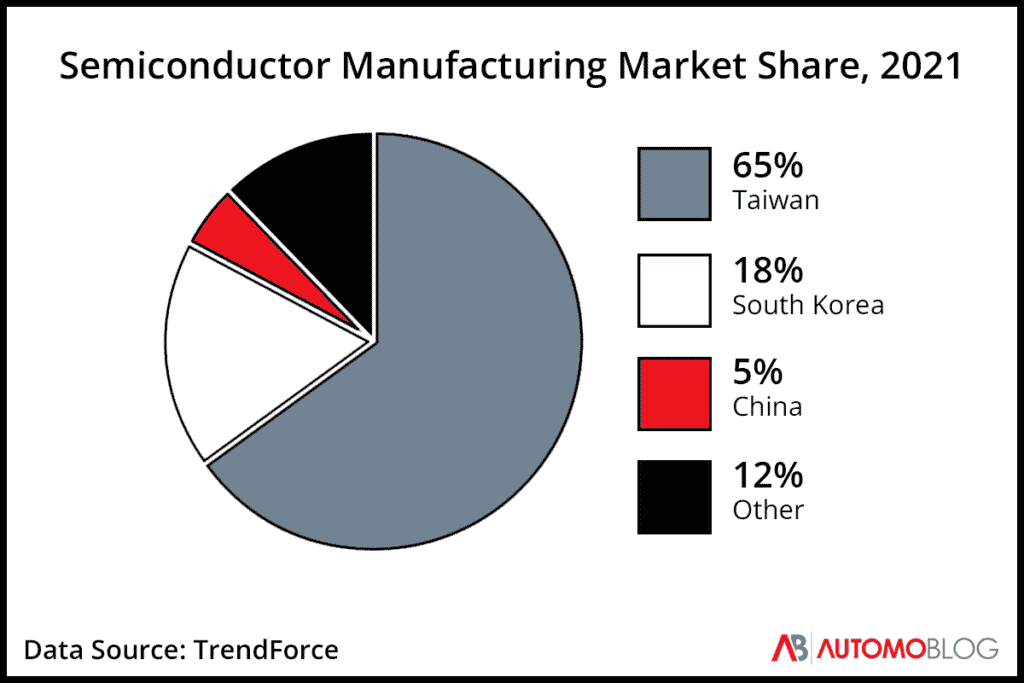

Another consideration is that the end of the chip shortage for one country may not, in fact, be the end of the chip shortage for all countries. To date, Taiwan alone accounts for 65% of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing market share. East Asia, as a region, accounts for 88%.

Even with an aggressive expansion of domestic production in the U.S. and EU, the world will be dependent on Asian chip manufacturers for a long time to come.

Hoopes suggests that as manufacturing and supply chains develop in some parts of the world, political and business forces could lead to greater semiconductor inequality.

“Plants that have, to date, supplied the world’s needs, may only supply specialty parts or primarily regional customers,” says Hoopes. “In fact, one possible downside of the distribution of chip manufacturing may be the end of what has been a globally integrated industry.”

The end of that model, she says, could result “in ‘nationalistic’ competitive tendencies of individual countries producing for domestic industries such as defense, auto manufacturing, and healthcare. This could cause shortages in some regions and surpluses in others.”

When Will the Chip Shortage End for Cars?

The question of when the chip shortage will actually end for car manufacturers continues to be a complex one. Whether the semiconductor shortage will draw to a close later this year, as Counterpoint Research suggests – or continue into 2024, per Gelsinger’s predictions – depends heavily on key infrastructural, economic, and political variables. If recent history has provided any lessons to chip manufacturers and the world at large, it’s that these variables are anything but predictable in the contemporary climate.